Storm at sea

I hold a secret in my deep

so grey and old.

The sea cries out my hidden words.

Demanding to the cloud - and yet it dies -

zinc meeting zinc.

The storm is where my secret lies

So longingly.

Within the roar, the words are sung.

So soft they fall, within the misting dark.

Nothing to hear.

The storm departs the sky, too soon.

And then they fail.

Look close between the waves and see

the echo, sunlight smiling on the foam.

Words washed away.

Seven for a secret, never to be told.

On aesthetic culture: the argument from politics and religion.

How Nature always does contrive--Fal, lal, la!

That every boy and every gal

That's born into the world alive

Is either a little Liberal

Or else a little Conservative!

On graveyards

Media vita in morte sumus - in the midst of life, we are in death, says the English funeral service of Thomas Cranmer. Nowhere is this seen better than in a churchyard, with the dead lying - with their feet to the east, ready to face the resurrection - around the church. Yet this does not seem quite right: here, the dead are in the midst of the living. And in the churchyard grows rich and fecund nature, irrepressible despite attempts to hold it back. Here there is a pathetic progression from the brightest clear-cut gravestones, honoured with carnations, back into the mottled old slabs of the previous generations, where the flowers fade and disappear. Once they too were revered by those who now lie beside them - and we, the living, walk amongst them all - in to the church and out to the village.

Entering into the world

Evolution or God – a fair question?

”The year which has passed has not, indeed, been marked by any of those striking discoveries which at once revolutionize, so to speak, the department of science on which they bear"

So wrote Thomas Bell in his review of the scientific year of 1858. As president of one of the most eminent biological associations, the Linnean Society, one might have thought he would be in a position to know. Yet in July of that year, Charles Darwin and Alfred Wallace had presented a joint paper to that society that laid out the principles behind what was to become one of the most famous scientific theories of all time – the theory of evolution by natural selection. Although Darwin had been known to have been quietly working on a theory of evolution for many years, the revelation to him that Wallace, working in far-off Malay, had also arrived at similar conclusions compelled him finally to publish. Thus came about, along with Newton’s Principia and Galileo’s ” Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems”, one of the few truly famous works of science – Darwin’s “On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life” (to give it its full and correct title), published 24th November 1859 – this time to a storm of interest.

Why was it that Darwin’s theory created so much interest and controversy? He was by no means the first to propose an evolutionary theory – such ideas had been slowly drifting around in and out of the scientific establishment since the 18th century. But both he and Wallace – a respected naturalist in his own right – had had the opportunity to do something that previous workers largely had not – to travel broadly around the world and closely observe the workings of nature. It was this broadened understanding of the natural world – seeing how animals and plants interacted with each other and with the environment – that opened up the possibility for proposing a serious mechanism for how this astonishing diversity had come about. Darwin was thus not only the first serious evolutionary thinker, but also the first ecologist.

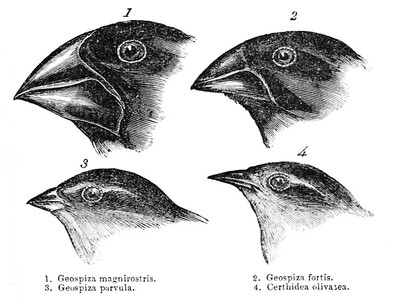

Why did Darwin come to the conclusions he did? One of the most important reasons was that he came to see that the distribution of organisms was closely related both to their environment and to their own close relatives. It became clear to him, after the landmark voyage of the Beagle in the 1830s, that very closely related species were not randomly scattered around, but instead lived right next to each other, typically separated by barriers such as mountains, rivers or the ocean. This was most clear in systems of islands such as the Galapagos, where the famous example of Darwin's finches – a group of closely-related birds - was found. Oddly enough, Darwin seems not to have been too interested in these iconic birds at the time of the voyage itself, but rather came to see their significance a few years later. In particular, what struck him was that despite their unique occurrence in the Galapagos archipelago, they were unmistakably similar to birds also found on the nearby South American mainland. Why would it be that such similar birds would be found just there and in the Galapagos, when the environments were so different? By the time of the second edition of his book The Voyage of the Beagle in 1845, Darwin felt able to hint at his slowly forming theory when he wrote “Seeing this gradation and diversity of structure in one small, intimately related group of birds, one might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one species had been taken and modified for different ends”. In other words, just as he came to see that the species of the Cape Verde islands had spread there from Africa, forming new species as they adapted to their new environment, so the Darwin finches were all descended from a single species that had managed to cross the 600 miles from present-day Ecuador to the Galapagos, evolving as they spread from one island to the next. It was exactly this sort of detailed observation and data that gave Darwin's theory the solid backing that the vague ideas of previous thinkers had lacked. Around these observations coalesced many others – the distribution of fossils in the rock record, the presence of apparently non-functional organs in related organisms of which the most well-known was probably our own appendix, and the ability of human breeders to mould and shape domestic animals to produce more meat, wool, or simply to look spectacularly different – ideas that after the agricultural revolution of the 18th century could hardly fail to impress.

Darwin had originally planned to write some enormous monograph on natural selection, but his discovery that Wallace was working towards similar ideas pushed him into early publication of what might be called an abstract of the longer work which would doubtlessly have been full of references, notes and the rest of the typical scholarly apparatus. This work in its entirety was never to appear; and thus Darwin's most famous contribution to science has a rather unusual flavour. Somewhat anecdotal without being sensationalistic, it was written for a popular audience but yet contained serious science by someone who even before its publication was highly respected and whose fame (unlike the lesser-known Wallace) virtually guaranteed that it would be taken seriously. It's often said that the Origin of Species is the most accessible of all the great works of science, and while this is probably true, the average reader coming to it is likely to be dismayed by some fairly difficult passages, especially a particularly gruesome discussion of fancy pigeons (which Darwin had something of an obsession with) that occurs right at the beginning. If one perseveres through this though, a remarkable – and remarkably modern-reading – set of sharp observations and shrewd conclusions follows, still a mine of interesting evolutionary thought for the modern scientist.

I shall turn to the religious reaction to Darwin in a moment, but what about the scientific one? Darwin's thought was in many important ways not a cause, but a product of his times, and various sometimes sensational publications in the years before the Origin had brought the idea that species could change through time into respectable scientific spheres. In many other ways, too, the idea that species were not creations of God in a short period a few thousand years ago was becoming easier to accept. Pioneeering geologists – including the Reverend William Buckland in Oxford and the Reverend Adam Sedgwick in Cambridge - slowly built on ideas that had emerged at the end of the 18th century to show that a universal flood could no longer tenably be thought to be responsible for the layers of rocks with their characteristic fossils. And from the pens of writers such as Hutton and Lyell came compelling data and texts that showed the earth, far from being of recent origin, had instead existed through countless eons of time. Given the earth's apparently endlessly cycling through such unimaginable time, when deserts could seen once to have existed in Devon and vast coally swamps to have covered much of Europe, the idea of species staying constant whilst all around them was in flux started to fade. Early consternation was caused by the discovery by Cuvier in France that certain types of animals had apparently gone extinct, in direct contradiction to 18th century ideas of the perfection of nature – the “best of all possible worlds”. And perhaps most important of all, the work of the early German critics of the Biblical texts – the so-called “higher criticism” - weakened adherence to a literal reading of the cosmogeny of Genesis. The problems were greater than simply knowing who Cain's wife was. The realisation that the bible contained a great number of different types of writing – history, law, poetry and many others, raised the revolutionary idea that perhaps reading these texts as if they had been written by modern scientists with their particular preconceptions and interests was highly anachronistic. The time was ripe for Darwin to step hesitantly and modestly onto stage.

Although initial reaction to what quickly became known as “Darwinism” was in many quarters quite hostile, by the 1870s, the idea of evolution – the transmutation of species – was widely accepted in the scientific world. Some scientists indeed thought that Darwin, by choosing to publish in this somewhat unconventional way, had abandoned the solid foundations of building on a mass of data in favour of rather uncontrolled speculation, but as more evidence about the natural world came to light, such objections were slowly silenced. More important reactions came from the palaeontologists, who were often opposed to Darwin because the fossil record did not seem to support the slow and gradual change that his theory seemed to demand – a topic that arose again in the 1970s in a somewhat different guise under the name of Punctuated Equilibrium that excited much controversy in the following twenty years. Nevertheless, it is perhaps not so well-known as it should be that by the end of the 19th century, Darwin's own contribution to evolutionary theory – Natural Selection, the words that stood in the title of his remarkable book – was largely discredited, and remained so for something like half a century. Thus, the very reason by which Darwin thought he could prove evolution to be true was quickly discarded by those he persuaded of evolution.

Darwin's problem was that he knew of no good mechanism for the core requirement of his theory, that the attributes of organisms that gave them the ability to compete successfully against their less fit fellows could be passed on to their offspring in a way that could preserve them, rather than just swamping them out in countless other more useless features. Darwin's own theory about this was speculative and (it turned out) tiresomely wrong. Shortly after the Origin was published, Gregor Mendel, an Austrian friar working in the garden of his abbey, produced the key: variations in plants did not blend in their offspring, but were rather inherited discretely, in an “either-or” manner, thus allowing Darwinian natural selection to work on them. When this work was rediscovered at the end of the century, it at first rather ironically added another nail to Darwin's theory though: the size of the mutations Mendel described seemed incompatible with Darwin's ideas of imperceptible change leading slowly to adaptation. By the first two decades of the twentieth century then, Darwin's ideas about evolution were in almost total eclipse, only to be revived by the technical mathematical formulations that both triumphantly vindicated him and gave rise to the so-called “Neodarwinian Synthesis” that is the cornerstone of modern biology.

I've given this very short introduction to the origin of the Origin, so to speak, not because I've forgotten that I'm not standing in a university lecture, but because I want to emphasise how ordinary it all was. The controversy that has always existed about evolution has given the whole subject a curious status all of its own, lifted out of the normal run of science by its apparent direct challenge to theistic ways of thinking about the world. What really happened was this: the voyages of discovery of natural history undertaken in the first third of the nineteenth century, and the first really investigation of the geological record, revealed a world that was clearly not compatible with traditional ways of thinking: and under such pressure, everyone's ideas perforce changed. In this sense, the Darwinian revolution – for such it was – is cut of exactly the same cloth as all other really major advances in scientific thought: not driven primarily by ideology, but by simply trying to get to the bottom of what the evidence was really saying. Given that regularities exist in the world, it is inevitable that scientific theories can be made to encompass them.

How did the religious world, then, react to this remarkable work? As one might imagine, the reaction was a mixed bag. It can be summed up as resistance by the conservatives, welcome by the liberals, and (of course) a hesitant dither by the large body of moderates. Not much changes. Yet resistance was – in retrospect – perhaps nowhere near as strenuous as might be imagined. The trouble was that the theologians had managed to get themselves into something of a tangle without any help from Darwin. During the nineteenth century, it became obvious from the rocks that each period of time was characterised by a particular set of organisms. In the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, dinosaurs had roamed around in the South of England; in the Cambrian, trilobites had swum around in Wales. In the sort of compromise that rarely works (despite its enduring popularity), a theology of “special creations” was cobbled together, which smeared the creative acts of Genesis through various “eras”, a protracted creation punctuated by gigantic cataclysms that wiped out the previous inhabitants of the globe. The last of these misfortunes was taken to be the Flood; an idea that was reluctantly abandoned when the realisation set in that the deposits in question could be reliably attributed instead to the Ice Ages. In any case, in what way was such a theological theory any more compatible with the biblical record than what the scientists were coming up with? This realisation, that without some theory of evolution, understanding of the world simply became a blank, was much responsible for the perhaps surprising acceptance of evolution by the mainstream of the Church of England at least, from being mostly hostile in the 1860s (but then, many scientists were as well), through to gradual acceptance from the 1870s onwards. It should not be forgotten, after all, that when Darwin died in 1882, he was buried with all honour and ceremony in Westminster Abbey; and the committee for the memorial fund for Darwin had the Archbishops of Canterbury and York as members. Even the Roman Catholic Church, which was notably stern on such matters, just about kept its official silence until its declaration in 1950 that, as far as it went, and with some important qualifications, Darwinism was not incompatible with the faith.

Nevertheless, despite this apparent acquiescence – indeed, in some quarters, such as by Charles Kingsley, the author of the Water Babies, the positive welcoming, of evolution, it would be wrong to characterise these early years as being all smooth sailing. As society became increasingly secular, and perhaps more important, as the study of the natural world stopped being the preserve of country parsons with not enough to do, and became instead the job of professional scientists, a gap started to grow being the churches and the scientists. At one level, this was deliberate – Huxley, Darwin's Bulldog, was a great champion of the intellectual freedom of scientists, unrestricted by theological disapproval, and did much to create and nourish a new class of professional scientists. In the turbulent years of the 1870s and and up to the 1890s, two books in particular were published, by John Draper and Andrew White that, by a tendentious historical survey of the relationship between science and religion, attempted to show that the dark oppression of religious dogma stood in stark opposition to the bright light shown by fearless science that ever falls on the path towards truth. Although Draper's book in particular is little more than an anti-Catholic rant, and although both books are dismissed as being essentially polemics with little or no historical value by modern historians of science, their influence was deep and prolonged – even today their ideas circulate very freely on the internet and are vigorously defended by those inclined to such things. They are both, of course, absolutely awful books. They were influential in generating the myth, so common today, that science and religion have always stood in warring contrast to each other, and it is true that one can find people then, and now, who will say that Darwinism destroyed their faith. However, the exact reasons for this apparent incompatibility are much harder to explore – there was more a general feeling for some that that was the case than a crisp and easily stated case. Indeed, when pressed about exactly what it is about natural selection and science in general that somehow rules out a religious understanding of the world, one often finds the answer simply dissolving into vague comments about how unpleasant the world actually is, of which more in a moment.

So at last I can come up to the recent and think a little about the present-day conflicts that have been so prominent in recent years, driven of course by prominent opponents of religion such as Richard Dawkins. The reason that I have not mentioned this name before – perhaps you expected it in the first sentence! - was that I think it's somewhat important to put the modern disputes into some sort of context.

Like some thinkers of the nineteenth century (but perhaps surprisingly, not that many so far as one can document at least), Dawkins writes that his childhood and adolescent christian faith was shipwrecked by his discovery of natural selection. The extraordinary diversity and beauty of the natural world, with all its intricate interactions and balances, can be best seen, not as the direct work of a master craftsman – a divine watchmaker – but as the meaningless outcome of an enormously long period of selective processes. With considerable skill, Dawkins and other prominent evolutionary thinkers have shown that even the most remarkable organisms and their behaviours need not be attributed to special creation, but can be very fairly be regarded as the product of blind selective processes. Indeed, the title of Dawkin's first, and in many ways most successful books is the Blind Watchmaker, and although both scientifically and theologically I have many differences with him, I am happy to acknowledge the debt I myself owe to this work. In it, he shows in the most robust way imaginable that the imagined scientific objections to natural selection as the principle driver of evolution are largely based on a misunderstanding of the theory. Indeed, what natural selection fully means in a scientific sense remains rather poorly understood even amongst the scientific community – even, one might say, amongst biologists. It is without doubt an extremely powerful theory that has all sort of remarkable ramifications that are still the object of active research. But if natural selection has such explanatory power, then how (one might ask, as Richard Dawkins did in his debate with the Archbishop of Canterbury of Canterbury the other day) does one squeeze God into the picture? What is it that God is meant to be doing in all this? Isn't it really, then, a straightforward choice, between a powerful and well-demonstrated scientific theory, that of natural selection, and a rather more flaky one, that of God, whom after all the only person to ever see was Moses, and even then only the “back parts”, after all?

I think the problem that scientists have with religion and science (the minority, that is, that have thought in any way seriously about the matter) is that to them, it seems that religion sometimes reserves to itself the right to make scientific statements about the world, irrespective of what physical evidence suggests. The dismal story of so-called creation science is illustrative of this. By taking the early parts of Genesis in a strictly literal sense, one might then say that the bible gives a straightforward scientific narrative of who the world came into being – first light, then the heavens, then dry land and the plants, then the animals and birds of the oceans and air, then the livestock of dry land, and finally humans. But we have known for about 200 years at least now that this reading of Genesis is simply untrue – it does not correspond in any interesting way to how the world appears to be (and that is, after all, the only we can take the world, as it appears!). That was the anxiety generated in the nineteenth century – it became obvious that what the bible taught, or was thought to teach, was not true – and if not true at this point, why should it be trusted elsewhere? Similar worries underly much of the modern religious resistance to evolution, I think. When one looks at Genesis a little harder though, a few more interesting things to reflect on emerge. The first is that there appears to be two different creation stories combined in the first three chapters, one about the six days of creation, and the other about the creation of man and woman, the garden of Eden and the fall. Certain elements of incompatibility remain between these different accounts, but it is notable that final editors did not feel the urge to remove or soften them, suggesting that whatever their intent was, it was not to create a fully unified scientific account of creation. And the second is that, when compared to other creation stories of the same sort of era as Genesis, what is wholly remarkable is how little Genesis says. Genesis says hardly anything about the actual acts of creation, but merely declares God to have created the world. The fussy details present in other stories, such as the importance of huge magical eggs, or dismembered giants, or floating masses of jelly (as in the Japanese creation), are all pared away in the final version of Genesis that came down to us, and the text simply and majestically declares: “In the beginning, God created heaven and earth” - a masterpiece of restraint whose remarkable nature is hidden by only its familiarity. Finally, one might note also that the profoundly ethical view that the ancient Hebrews had of the world is also overlain on the stories from the start: the wrongdoing of Adam and Eve in taking the forbidden fruit; the declaration of the crime of Cain in murdering Abel; and most startlingly, the wrongdoing of humans as a whole that leads to its almost entire destruction in the flood. It is easy to take these early acts of punishment as signs of a brutal and vengeful god until once again, one sees the alternative versions. For example, in the flood story of Babylon, in the Epic of Gilgamesh, the gods destroy humankind, not because of their sinfulness, but simply because they become annoyed by all the noise the humans are making! One might think that what we are seeing here is the reflection of early societies on catastrophes that afflicted them: the Hebrews were almost unique in the ancient world in seeing them in primarily non-magical and ethical ways. They took a story they probably inherited and softened it in various ways: by adding an ethical reason for the appalling events, and in one of the most tender moments in the entire bible, by the addition of a poignant touch: that God closes up the door of the Ark behind Noah and his family. Thus, a capricious story of destruction is deftly turned instead into one of tender rescue.

I digress somewhat. But the reason for doing so is that the modern obsession about the first 11 chapters of Genesis, which harps continuously about their scientific inaccuracies and impossibilities, to me entirely misses their point (these chapters are to me some of the most extraordinary writings to have been preserved from the ancient world). Rather than being a scientific account – which in any case was not even a way that anyone would think about the world for another 2000 years or so after they were finally brought together - they are a profound ethical and psychological reflection on what it is to be human in a world full of danger, injustice and suffering – a suitable topic for pondering in Lent, indeed.

I don't think, then, that Christianity should be disturbed by the discovery that the formation of the world was not as traditionally thought. But is that the end of the story? I don't think so. If we accept that the living world – and deeply embedded in it, that includes humans of course – emerged as the result of many millions of years of slow evolution caused by the blind processes of natural selection, then where does that leave the insight of Genesis, that this world, beautiful but tragically imperfect, was the work of God, in a labour so profound that even God rested on the day after its completion? If we are to retreat from the providential view that God somehow made special sorts of direct interventions to fill in alleged gaps in scientific understanding, shouldn't we be compelled to eliminate God all together? Isn't it actually a fair question to ask if we have to choose Evolution or God? This is a common narrative indeed today, and the answer we are supposed to choose is coming loud and clear from the usual suspects.

I want to ask a few questions , then, that might lead to some sort of response to these issues. And the first question I want to ask is: what do we actually mean, even as Christians, by creation? This fairly obvious question seems to me to lie at the heart of many misunderstandings, both by the religious and atheists. For there seems to be a persistent attempt to see God as part of the causal chain of Nature – by creationists who insist that special divine interventions must characterize particular parts of the formation and evolution of the world (including, one might add, dictation of the first chapters of Genesis!), and by scientifically-minded atheists who insist that any God must be in some way measurable against the standards of the world supposed to have been created by it. For despite the point being often denied, it's hard to avoid the conclusion that recent writers consistently see God as something like a super-strong or powerful version of a human, or electricity, or gravity or somesuch. Seen in this light, of course, neither creation nor God guiding evolution in any way make any sense at all – rather than solving the problem of creation, the postulation of a God simply exemplifies it – and, one might think, in spades too. Such a God not only adds nothing interesting to our account of the world, it actually makes the world intolerably hard to explain, and thus gives up all the hard-won scientific advances we have made in the last two hundred years or so. I give this round to Dawkins – but this is not the end of the question. For to have a real doctrine of creation – of God making something new, must surely involve something else too: God must make some space for there to be creation at all. For if God is all in all, how can there be genuine creation, the making of something that is more than simply a sub-department of God? Such ideas have been explored by the Jewish theologian Isaac Luria, who talks mysteriously about the “shrinkage” of God, of a deliberate limitation of God by Himself to create something that can be considered to be something truly apart from God Himself. No wonder he rested on the seventh day. And although such views have hardly been considered by Christian theologians (Moltmann being an exception), such a view – that God's work of creation involved voluntarily-entered self-limitation, even humiliation, fits well with Christian Lenten reflections of the work of the cross too, which reveals a similar movement. Thus, although some christian theologians and some scientists have pondered God's acts in creation as acts of power – with the secondary question of how such a being could both exist and exercise this power, a more truly Christian (and indeed Jewish) understanding of this stupendous work is not as an act of power (for if so, there would be not true creation at all), but rather an act that embodies the traditional “theological” virtues of faith, hope, and love: not our faith, hope and love, but God's. For God to truly to create – to make something truly different – God must give up power, and thus inevitably the creation cannot fully reflect the will of God. Paradoxically, only by giving up power can God then be free to act within a creation. Or to put in an even more recognisably Christian form: God does not run the world, but sustains and cares for it. The God of power turns out not to be God at all, but merely one created thing among others. So at all costs, Christians must resist the temptation to see God as a mechanism of the world, that can be investigated like rainfall patterns or how the liver works.

When the evolutionary biologist J.B.S. Haldane was (apocryphally) asked about what could be learnt about the mind of the Creator from the creation, he is meant to have replied "An inordinate fondness for beetles”. And there are indeed an enormous number of beetles. More seriously though, one way in which science has helped theology to think about the creation seriously is by revealing the truth about what it is actually like, and this truth is not always comfortable for us to bear. St Francis of Assisi could write movingly, in his hymn of the creation, the “Canticle of the Sun”, about how contemplation of the natural world leads to praise of the creator, but this sentiment can sometimes seem naive today. We know that the natural order that emerges through natural selection is not always a nice one – animals and birds routinely allow their weakest offspring to starve or be abandoned, parasites inflict untold and horrible suffering, and even the sexes war amongst themselves in the endless battle to pass on the best genes. For those only interested in the God of power – the God of micromanagement, one might say – such patterns create a profound problem. To what extent are we to affirm that even paralysed caterpillars being eaten from the inside by parasitic grubs are the direct work and intention of a loving God? It was precisely these sorts of contemplations that seem to have slowly turned Darwin himself away from religion and the old sense of providence, of God's caring intervention in the world. And I think at the end, the objections many scientists have to a religious view of the world come down to this: their objections turn out not to be scientific (these objections seem to be impossible to crystallise when one asks hard questions about them), but about the oldest problem for the theist of all: the problem of evil. And this is where the problem with the new atheists for me reaches its critical point. Here is a quotation from Richard Dawkins on the topic: “The universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil and no good, nothing but blind pitiless indifference.” Now what I want to know is – and I think it is a question to be urgently asked – what sort of statement is this? Is it a scientific statement, judged against the control of a world where we know God exists? Or to put it more crudely, how on earth could someone know something like that unless they had an exceptionally clear view of what a created world would be like? Once one allows, as I have argued, that any creation worth the name must be free, then surely this is not an absolute but a relative question – a subjective, not a scientific judgement. And that is precisely the judgement that the Christian is invited to make – so see the world, despite everything, as God's good world.

For there is surely another side to this story too. The most materialist scientists are given to wonder at the glories of the creation, and even parasites can possess an extraordinary power to fascinate. There is, as Darwin noted in the famous closing passage of the Origin, a grandeur in this view of life. Perhaps it is after all possible to come to a chastened appreciation of the creation, in which (as even St Francis says in his canticle) the place of suffering and death can take their right place along side the simple child-like pleasures afforded by watching young animals play, or finding the first snowdrops of spring.

Perhaps what I have said just now may been as some sort of evasion, of a polite stepping-around of the vexed question of God's action in nature. If we allow that everything that happens is in a sense natural, then in what sense is God involved in the world at all? Isn't it after all simpler to leave that component out? I think the answer to this – which will certainly not be a scientific one – must come back to our own place in the creation, the moral implications of which so exercised the Victorians. For surely the key in all this is our own view of the matter, our worry about the loss of diversity and the destruction of habitats, and the remarkable efforts we sometimes make to preserve them, and the endless appreciation of, and sublime joy we can take in nature. These acts of curation are not, if we are honest, the simple outcome of scientific considerations. They surely reflect a view, not just of self-preservation, but of worth: we profoundly see the world as worthy of care. And if we can manage to come to an appreciation both of the natural world and of our own lives in it, despite all the horrors that it can contain, perhaps it is not so much of a big step to think of that appreciation residing also in the other organisms that live there, parasites and predators notwithstanding. So despite the extraordinary mechanism that Darwin and Wallace discovered that materially brought about this world, isn't it still possible to see the entire thing as God's world, the world brought ultimately by divine love in action? We might come to see then that the question of how God works in the world – how God brings about good, and defeats evil, is not something to be resolved at the level of micromanagement, of God pushing atoms around or causing cunning mutations at just the right time and place. Rather, any answer may lie in having the patience to step back from the scientific bustle and to think, as St Paul does in his letter to the Romans, of the entire creation waiting for its final redemption, a redemption for which it groans with impatience for.

For some, the suffering in and of the world will be too much for them to take this step, but Christian hope will have no part in this loss of faith. And here, science and religion, rather than being warring enemies, are revealed as partners, both willing to see the world as a place of wonder rather than of horror, both acting to preserve and nourish the good in it. And I believe that someone like Richard Dawkins, despite everything, actually shares this basic sense of goodness in the world in fact, as his more lyrical passages suggest. So perhaps there really is hope for everyone.

On minimalism

Actually, the film is pretty sanitised: in reality, the "Leonard" character, far from conducting a graceful love affair, demanded to be sent to a prostitute, and spent a good deal of his waking time (furiously?) masturbating.

Olds and Milner in the 1950s showed that rats, given the choice of eating or stimulating the pleasure centres in their brains, will simply do the latter until they drop dead of starvation or exhaustion (so it is said, anyway: I can't really find this in their famous 1954 paper). Rats normally hate electrical shocks, even mild ones, and will starve, rather than walk across an electric grid for food water or sex. But if the button to stimulate their pleasure centre is across the electric grid, they simply walk across it as if it were not there. And humans themselves have some notoriously addictive behaviours which are rather similar (e.g. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/scienceandte ... caine.html)

Indeed, in the famous work on the Dialectic of Enightenment by Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, a discussion of the dark side of the Enlightenment, de Sade is championed as the logical end of the Enlightenment: he reduces everything, rationally, to the two concrete things in the world: his own power and his own pleasure. Enlightenment Man indeed. Perhaps it is no coincidence that 120 Days of Sodom and Kant's Critique of Practical Reason were published within a few months of each other. “Nature has radicated in our spirit only one commandment: that of enjoying; no matter how, no matter at whose expense”, as one of de Sade's characters says. And he is nothing if not systematic. Ah yes, he covers paedophilia, of course. With effort, and discipline.

But (perhaps fortunately, although I pass no judgement right now) that is not the end of the matter. Because there are other aspects of life that do not revolve purely around the immediacy of power and pleasure. Nor are these made more meaningful by the knowledge of the limitations that death brings to everything.

Those more reflective activities, such as the commitment in a long relationship of love, are closer to what I mean here. It is customary to complain about postmodernism: but the truth of the matter is that we are all in its grip now. This is why "serious" composers can no longer use Neapolitan relationships, as say, Mozart could to such moving effect; or why it is so difficult to say "I love you" without a twinge of irony. We seem to have used these artificial resources up long ago, just as we are using up natural resources now. When Beethoven wrote his noble and optimistic ”first” piano concerto, he was not yet under the gloomy pall of such cynicism: but now everything is. What then was fresh and joyous is now sentimental and derivative. Not even I appreciate the sentimental.

Despite this modern malaise, humans do in fact sometimes manage to break free of these constraints: but this comes at a cost. To be in love is, after all, to open yourself up to the inevitability of the suffering and death of the other person; yet our commitments of love do not - cannot - take this into account. To love fully is simply to open yourself to the inevitability of ultimate loss. To allow the pleasure that nature can give - a pleasure that is not, like de Sade's, dependent on the exercise of power - is to resolutely refuse to give oneself up to the dystopian frozen moments of the late Romantics; where the knowledge of final loss tinges every joy with sadness. This is truly to live in a sort of reverse eschatology, where the knowledge of the end is brought endlessly into the here and now, so that after the flush of youth is gone, one literally sits and waits to die, as one already dead.

In short: to love someone or to listen to the dawn chorus in the spring, or even to drink too much at the wedding of a friend, is to live in endless vernal hope: they are not anxious pleasures driven by the knowledge of the coming of death.

Insofar as we live hopefully, we show a certain, what, commitment, towards taking a happy view of life, despite everything. Or, to put it another way, we express some degree of happiness with our own strange being-in-the-world, the particular and unique circumstances that surround us in the here and now. We do not need to do this; but if we do, we are (at last it comes) expressing a certain aesthetic judgement towards our being. This is not an attitude of denial, but of waiting; not of delusion, but a clear eyed joy. This, I submit, is one of the bases of religious belief. And note that religious belief comes not evasively, as a way of evading the uncomfortable consequences of our own mortality, but positively, as a rational summing up of a particular type of joy. It is our own sense of being that allows such a taking of responsibility for ourselves, that allows us to align ourselves in such a way. It may be that one day that this responsibility will one day be taken away from us, with the final elucidation of the neurological basis for "consciousness". This may one day happen; but as I have said before, we will certainly be different creatures then. But this wish is just the reversed eschatology smuggled in once more; bronze weapons clanking ominously in the wooden horse.

Out of this, incidentally, comes one of two distinct challenges to Nietzsche: it gives the lie to the idea that Christianity crushed the Dionysian joy from life. Insofar as it did, it was untrue to itself and its own gospels, full as they are of the images of the kingdom of heaven being a Jewish wedding where, after all the wine runs out, an endless supply of the best is revealed. I was in Rome a few weeks ago and down in the catacombs, underground where millions lie dead. These dank corridors should be the exemplars of Nietzsche’s critique: hidden from the light, deeply buried resentment. But they are not, as the frescos bear witness to. Both the beginning and end of the gospels are about joy: there is no hint of the grey breath of the killjoy galilean there.

The solidarity of the aesthetics of loneliness

On nostalgia

On Science and religion (i).The mimetics of desire.

"It is possible that mankind is on the threshold of a golden age; but, if so, it will be necessary first to slay the dragon that guards the door, and this dragon is religion."

Bertrand Russell.

I wish to start writing about one of the great issues of our age: the conflict between science and religion. I is remarkable how easily, how smoothly, how enticingly, it fits into Girard's theory of mimesis. For in the modern world, science and religion are struggling for the same thing; influence, the right to arbritrate about what is true, and who are; how even to raise children. As they both reach for the same object, conflict is inevitable.

The atrocities of religion are well known, so I want to focus a little on science. In any conflict, as it deepens, guilt must rise as violence ensues, so a rationalisation must take place, in the form of diminishing the enemy. This can take place in two ways: accusing it of bestiality and monstrosity - of being subhuman or of being evil. And indeed, in the onslaught on religion launched by the self-proclaimed "brights" we see both these tendencies, ignoring the fact that the accusations are mutually incompatible. In the first instance religion is seen as irrational and childish; in the second, as evil: accusations of child abuse and paedophilia; violence, murderous rage and so on are bandied about remarkably freely. Here is Dawkins in the God of the OT: "arguably the most unpleasant character in all fiction: jealous and proud of it; a petty, unjust, unforgiving control-freak; a vindictive, bloodthirsty ethnic cleanser; a misogynistic, homophobic, racist, infanticidal, genocidal, filicidal, pestilential, megalomaniacal, sadomasochistic, capriciously malevolent bully". How can we treat our brothers and sisters in such a way? It is the slander of the ages.

Meanwhile, religion also reacts, in equally aggressive ways. Both protagonists, in their attempt to differentiate themselves from the other - to "gain the upper hand" thus merely manage to imitate each other until they are virtually indistinguishable - the monstrous double, as Girard calls it. And within this conflict emerges the attempts to scapegoat, of which Russell's quotation with which I opened is so blatant that it hardly requires exegesis (notice the explicit language of violence it employs). If only, the argument runs, we could expell the evil from among us! Then we would finally have peace. But in so creating a victim we automatically endow it with the innocence of victimhood.

Of course, like all scapegoating this one is based on the oldest of all the self-deceptions man has indulged in throughout the ages. It is, indeed, the lie of culture. Dawkins, for example, obsessively attempts to conceal this by claiming that atheism is indeed peaceful, but his attempt, at the end of the atheist century that slaughtered hundreds of millions, would be comical if it were not so humiliating.

Here is the truth: it is not the scapegoat that causes our troubles: it is us. "What is truth?", asks the Johannine Pilate before going out to the crowd and announcing it, in a moment of supreme irony: that Jesus is innocent. The scapegoat mechanism is revealed in all its horror; two enemies, the Romans and Jews, identify a common threat and eliminate it. The mob is satisfied - for a while. How tragic that this blood-bought peace lasted less than a generation, with the final end being the destruction of the Jewish nation.

The Passion narratives, with their declaration of the truth of this, are of course regarded as being in the ultimate in self-contradictory nonsense by the brights. But, as often, art reveals the truth too; for example, de Zurbaran's Christ Crucified. Here, all truths are united: the truth of our own murderous instincts; the truth of God's decisive intervention to save us from them; the truth of the innocence of the scapegoat through the ages.

"In brilliant light and in a void of darkness, Christ is alone on the Cross. He is still alive: there is no wound in the side; he lifts his head; his lips are open; he is clearly speaking. Can we guess what he might be saying?

"Now the Gospels tell us that Christ spoke seven times from the Cross, but I believe Zurbaran has illustrated only one of these. Christ is not looking down, so he cannot be commending his mother to St John. Nor is it likely he is saying 'I thirst' to the others at the foot of the Cross. He is not looking to one side, so he is surely not telling the trusting thief that they will soon be together in Paradise.

"His eyes are turned upwards; he is speaking to his father in heaven. What is he saying? Is it the despairing cry reported by Mark and Matthew, 'My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?' or the more tranquil, 'Into thy hands I commend my spirit', that Luke gives us?

"I think it is none of these. These are words spoken in anguish and near the end. But here the beautiful body shows as yet few signs of physical distress. The agony of crucifixion seems to be only beginning. And Zurbaran is surely showing us the first of all of the words from the Cross: 'Father forgive them, for they know not what they do' (Luke 23:34). Christ is praying - for us.

"Pain makes most of us selfish - releasing us, we like to think, from any wider obligations - but not here. In the throes of his agony, this man achieves the divine. He intercedes for the salvation of others.

"And this, I think, is the point of the picture. The artist has contrived that we seem to stand at the foot of the Cross, closest to the brutally nailed feet, looking up at the body in pain, and we witness the very act of redemption, when Christ's suffering is most clearly revealed as a supreme gesture of love for us."

Neil McGregor, _Seeing Salvation: Images of Christ in Art_. 2000, BBC Worldwide Ltd.

I am often confronted with the relatively aggressive request to come up with a 'real' difference between humans and other animals. It's actually quite hard. Animals appear to be unhappy sometimes, to feel pain and confusion, to try hard to do things and fail, and even perhaps to think about the general rather than specific. But, though animals fear death when it comes to them, I do not think that even the other higher primates actually see their death coming; staring at them coldly and unwaveringly from the end of life. It touches all of our life, even our happiness. That tragic and terrible writer Miguel de Unamuno put it best, perhaps: "We are wont to feel the touch of anguish even in the midst of that which we call happiness, to which we cannot resign ourselves and before which we tremble. The happy who resign themselves to their apparent happiness, to a transitory happiness, seem to be as men without substance, or at any rate, men who have not discovered this substance in themselves, who have not touched it. Such men are usually incapable of loving or being loved, and they go through life without knowing either pain or bliss'.

To be "happy" in this life, then, is to resign oneself to its limitation; and as love really has no limitation, it is to resign oneself to a life without love: we cannot have love and happiness. But we long for both; fully to possess the mysterious joy that poets and mystics hint at, and which we glimpse every day in shadows falling across fields, or the shine of dew in a spider web, or the laughter of a child that I have already mentioned. We want it so desperately: its lack makes us inconsolable. In Sweden this sad longing is contained in the concept of 'vemod', the sense of melancholy that accompanies even the beautiful, but brave and brief summer here. Almost as soon as it is brought forth in full flower, the days are shortening towards winter once more: and its sweetness fades before our very eyes.

It seems to me that the contemplation of Christ on the Cross exactly captures this unbearable paradox. Even the most perfect life, the life most lived in wisdom, humility and love, ends not with a flight of angels and a chime of bells, but in a slurry of sweat and blood and defecation, in public humiliation. McGregor's comments above describe well the Church's view of this moment of revelation, of God come in redemptive glory. But there is another emotion that particularly Zurbaran's image evokes: not just gratitude, but also pity. Part of the mystery of the Cross is surely this: that it achieves the impossible of making us feel sorry for God. Unamuno again: "...suffering tells us that God exists and suffers; but it is the suffering of anguishing, the anguish of surviving and being eternal. Anguish discovers God to us and makes us love Him. To believe in God is to love Him, and to love him is to feel him suffering, to pity him."

The inescapability of death fills me with terror, despair and loathing, as it did Jesus. I long to live forever, so to grasp that eternal happiness, and fear that I will not: for I love life so very much. Yet that very anguish - and that love - is the engine of faith. Not because 'in despair' I invent God, but because in that very anguish I discover what it is to be God: God Himself showed us this on the Cross. He envelops our anguish with His own immeasurable anguish, says Unamuno. Yet in Christ's death we also see our own reflected and resumed, and so realise the Cross is not just a revelation of God; but also a revelation of humanity. The Son is put in the place of human suffering and sin, in the place of the need for redemption, and by contemplating Him we see our own condition. Is this, then, not God's greatest gift to the world - to show us his own suffering? And by pitying Him, do we not, as McGregor says, achieve the divine?

One day I will understand this mystery of the suffering God and suffering man, bound together in silent torture, and how it is that Easter Day triumphantly brings everything to the Good. But until then, I find myself looking up wonderingly and with pity at the foot of Zurbaran's beautiful and unbearable Cross, overshadowed with midday darkness. And in longing for God's ceaseless suffering to cease, I discover afresh my Redemption - and, perhaps, God's too.

The aesthetics of animals

Whatever the origins of domestication, the relationship of human societies to their animals sometimes far transcends mere utility. Some African cattle-herding tribes (such as the Nuer and Dinka) have such a close and intense relationship to their cows that symbiosis might be more appropriate to describe the connection. And in modern times, the rise of the environmental movement has made care for the animal (and plant) world a touchstone of popular morality. Indeed, even Kant, who did not view animal life very favourably (his philosophy is centred strongly on ration beings, a status he denied to animals) saw this very clearly: "He who is cruel to animals becomes hard also in his dealings with men. We can judge the heart of a man by his treatment of animals". Ed Wilson has elevated this idea into an evolutionary exploration of human instinctive inclination towards nature, in "Biophilia".

The aesthetics of religion (i): on lost works.

The cello is a difficult instrument to write concertos for: its normal register sits in the middle of the orchestra, which makes it difficult to make the solo part stand out: famous examples such as the Schumann one therefore tend to write for high registers. Still, the instrument seems to have had more than the usual bad luck.

Such works have at least some hold on our imagination; but what about works that might have been written by composers who died romantically young - notably Schubert (died age 32) and Mozart (died 35)? What operas, for example, would Mozart have written if he had lived to the same age that Monteverdi did, who produced his operatic masterpiece, the Coronation of Poppea, at the age of 75, with the Return of Ulysses the year before?

What I want to mention is our aesthetic response to such loss. One can indeed regret that such works never appeared; but we cannot miss them: aesthetic response is to subjective particulars, not to general ideas. Indeed, most people will never hear a Wagner opera, and despite their reputation as pinnacles of Western music, and thus music as a whole, most people who do hear them will probably dislike them. Furthermore, one's own taste can fluctuate through life: one can go many years without listening to a once favourite composer and then return to it again with renewed love.

One consequence of Kant's Antimony of Taste: the idea that we wish to universalise subjective aesthetic judgments, is that one cannot but feel that someone who does not appreciate, say, Parsifal, is missing something: their life would be better if they did. Naturally enough, this notion would typically be strongly, even violently resisted by the typical Wagner-uninterested person. It smacks of elitism, being patronising, and so on. Still, one cannot easily rid oneself of the notion, even if during a period of one's own life when such music did not interest you one did not feel necessarily impoverished.

I want to apply this sort of thought now to religion, the aesthetics of which I must now start to turn to.

Religion strikes me as occupying an intermediate position between science and art. It is a delicate path to tread, and one that is constantly in threat of being collapsed into one or the other: either being seen as just bad science, or as deluding art. Just as my tastes in particular music have waxed and waned over the years, so has my interest and participation in religion. Yet, even one if may not miss it doing the "off" periods, religion during its "on" moments is the great experience of life that all else is interpreted in; an ecstatic reinterpretation of experience and community; an "endlessly open epiphany", as Joyce's Ulysses has been described. Here is T. S. Eliot in Little Gidding:

"If you came this way,

Taking any route, starting from anywhere,

At any time or at any season,

It would always be the same: you would have to put off

Sense and notion. You are not here to verify,

Instruct yourself, or inform curiosity

Or carry report. You are here to kneel

Where prayer has been valid."

Religious experience, in all its humble beauty, is the great experience of life, and we should not abandon it under the pressure of those who despise it. Such should be resisted even more than that from those who despise the high tradition of music. Even if we know that such experience cannot be objectively demonstrated, and that those who once had it may despise it afterwards, we cannot but continue to think this, just as the case for Kantian aesthetics.

And so we come to the great problem of our age: how do we persuade others of the value of our own religious and aesthetic experiences? It cannot be by argument. It cannot be by demonstration: I cannot *show* someone my experience.

But perhaps Francis of Assisi was on the right track. Preach the gospel at all times. If necessary, use words.

On violence.

On religion and violence (i).

"The modern mind still cannot bring itself to acknowledge the basic principle behind that mechanism which, in a single decisive movement, curtails reciprocal violence and imposes structure on the community. Because of this willful blindness, modern thinkers continue to see religion as an isolate, wholly fictitious phenomenon cherished only by a few backward peoples or milieus. And these same thinkers can now project upon religion alone the responsibility for a violent projection of violence that truly pertains to all societies including our own. This attitude is seen at its most flagrant in the writing of that gentleman-ethnologist Sir James Frazer. Frazer, along with his rationalist colleagues and disciples, was perpetually engaged in a ritualistic expulsion and consummation of religion itself, which he used as a sort of scape-goat for all human thought. Frazer, like many another modern thinker, washed his hands of all the sordid acts perpetuated by religion, and pronounced himself free of all taint of superstition. He was evidently unaware that this act of handwashing has long been recognized as a purely intellectual, nonpolluting equivalent of some of the most ancient customs of mankind. His writings amount to a fanatical and superstitious dismissal of all the fanaticism and superstition he had spent the better part of a lifetime studying".

The aesthetics of cruelty.

We tend to associate art with beauty, although there are in fact many compelling works (Picasso's Guernica being a random example that springs to mind) that are anything but beautiful. But what about the association of aesthetics and cruelty?

I read recently about food customs in France throughout the ages; and in the medieval period the upper classes used to take the aesthetics of food preparation to extraordinary, if not repellent, levels. For example, an obsession about eating food freshly cooked developed, to the extent that in Avignon, geese were sometimes cooked alive. This was accomplished by placing them in specially constructed ovens with their heads sticking out, so that during the cooking process they could be fed and given water. The idea was to make the time of death and the time of being perfectly cooked coincide as closely as possible.

Such a story is of course revolting: but there is also, I think, something darkly amusing about it. But now try a slightly different, and even more sinister one. Many years ago now, I read an article about a professional torturer: it was based around an interview with him. He rather shrugged off the suffering he caused with a "just doing a job" sort of defence, which is not to say he did not have any sympathy with his victims. He said that, in extremis, as the torment became unbearable, the people he tortured all cried out for their mothers; and yet "they all died, slowly, slowly". This story has stayed with me for a long time now, but it is hard to unravel the response it evokes. Of course, there is a chill of horror associated with it, as one imagines being in that situation. But there is something else too; a sense of revelation. From such scenes of horror, we learn something about the "human condition", and there is indeed something profoundly moving about the primitive cry to the absent mother that harks back to studies on attachment behaviour that I have already referred to elsewhere. We are all made one by suffering, it seems to suggest; and while this is largely by diminution (defecating yourself with fear in front of a maniac with red hot torture instruments is not a revelation of the common nobility of humans) there is nevertheless something noble too.

For we have a complex picture: the torturer, proud of his "art"; the dreadful image of the man reduced to the child, and the endless sympathy this evokes in us. There is indeed beauty here, in the dreadful interplay between these. In some obscure way, I find something comforting here as well, although I am not sure what: I suspect that it is that in such a situation, we cannot but help feel a sense of empathy and indeed community with the victim. No matter who that person was - even your worst enemy, or even a torturer himself - in ultimate suffering that person is revealed as "one of us", crying out for his mother into the coming dark. But - is it not also true, if we are honest, that there is some hint of dark attraction about the intense cruelty of the torturer too - that there is really an aesthetic of the cruelty? To be in a situation where every taboo about the value of human is being broken, and by you, is there not some sort of dreadful dark joy involved in such a thing? Of course, it was Nietzsche - who else? - who investigated this in the Genealogy of Morals; claiming that watching others being tortured - or better still, doing it yourself - is an ancient celebratory act, an expression of the will to power, and he points to the "entertainments" that people had:

"In any case, it's not so long ago that people wouldn't think of an aristocratic wedding and folk festival in the grandest style without executions, tortures, or something like an auto-da-fé [burning at the stake], and similarly no noble household lacked creatures on whom people could vent their malice and cruel taunts without a second thought".

And he goes on to say:

"Watching suffering is good for people, making someone suffer is even better - that is a harsh principle, but an old, powerful, and human, all-too-human major principle, which, by the way, even the apes might perhaps agree with. For people say that, in thinking up bizarre cruelties, the apes already anticipate a great many human actions and are, as it were, an "audition." Without cruelty there is no celebration: that's what the oldest and longest era of human history teaches us -and with punishment, too, there is so much celebration! -".

Any account of humans and what drives them must, I think, take into account something like this. Which will not be without further implications.

God: a skeptic's guide in dialogue form (iii).

Protagonists: as before.

Day Three. At the restored Abbey of Monte Cassino, Italy.

Beda: Dear friends, I must thank you for agreeing to meet here, most momentous of places.

Johannes: Its is indeed a history mottled with grief as well as glory. How can we reconcile the two, the birthplace of quiet contemplation in Europe, with the desperate slaughters of more recent times? Perhaps eighty thousand died here. How tragic, too, that the ancient Abbey of old was destroyed to no avail; only sick monks lay there, and they most certainly bore no arms.

Petrus: I think we all stand silently before such a scene. No words can replace its own eloquence.

B: Yet recall its younger days, when the chants and silences of Benedict?s followers resounded through Europe: and that it was the first school of Aquinas, most rational of Christians.

P: Yes, he who tried in folly to prove the impossible: that God exists! And who thought he could prove the immortal soul ? again, a nonsense we have at last outgrown. Our modern studies of the mind have dismissed such fancy.

J: But, did not his adherence to the Philosopher of old temper this view?

B: It is true that Aquinas was no Cartesian. For him, the soul was the form of the body; intimately connected in every way.

J: But yet he thought we lived on after the body was laid in earth and corrupted?

B: This was his view. But note his careful words: only insofar as our intellect and volition are not dependent on our body is the soul immortal. Even in his view is the soul free from the body not complete: its reconciliation with the body is essential for its true operation.

P: You are a man of science, surely you must reject such views!

B: The sciences have indeed taught us much. Aquinas never knew the close connection we now do between mind and matter. Yet surely part of what he is aiming at is true. We know ourselves to be flesh and blood, knit together from the matter of the world: but yet, we look into the world from the outside: my thoughts are not atoms nor energies. To pretend otherwise as the modern materialists do is to do violence to both.

P: Then such things have no place in science!

B: Perhaps on this point we can agree. We will never capture the self in study of the world; it is experienced only as the window through which we peer into the world. It has no content to view; rather it is where we view from. Still, that does not allow us to abolish ourselves even so, even if we can say nothing more of ourselves.

J: You speak obscurely indeed.

P: Natural philosophers have searched through the world diligently for the supernatural, and have never found it.

B: Indeed, but what would they expect to find? And yet, the self falls into such a category if anything does. We intervene in the world without any causal mechanism, it seems. Yet no-one doubts we do so.

J: Your words tend to mysticism - I cannot comprehend their meaning!

B: Suppose it true that we are pure creatures of flesh and blood, our minds arise from the complex workings of our mind. Yet, to us, what difference does it make? We still live, and see, and think, and wonder. We can never see ourselves as some material thing. Our soul is not some sort of other matter: it is merely ourself.

J: So you mean that our soul is immune to the probings of science?

B: It is a point of view, not a thing. We can only remain silent.

P: Yet how could a point of view intervene in the world?

B: Not as a physical cause, of course: we do not push atoms around with our minds.

J: But then, how...

B: ...it is our doom or glory to think so. All the knowledge of the world will not alter our perception of ourself. We cannot imagine otherwise, and thus must accept it as practical truth, even without the theory of science - something, I think, that will never come. And if we see ourselves as such, then why cannot we see God as such - He who orders the turning of the endless stars, yet also is outside all causes? And thus, as we cannot abolish ourselves, we cannot do away with God either.

P: I will say this much: that I agree with you to the extent that our thoughts and feelings are not illusory. I am not one of those who would spirit them away, even if they emerge from the workings of the material world. Yet, when we die, as those who littered the ground around us did, we are gone for all time, never to return.

B: Let us agree that our end comes when our bodies return to dust. If we can have any hope, it must be of resurrection, not of living on. Yet that was the hope of Aquinas and Benedict.

P: But even if this could be so, why think so? We have no reason to think so!

B: We cannot deduce it from study of the world. All we can say is that that knowledge does not tell us to abandon hope either.

J: This topic has been perplexing, and the day has been hot. I would hear more of it, but not today.

B: I am sorry not to be more clear. This is a riddle that none can solve, only live in the light of.